How the Story Found Me

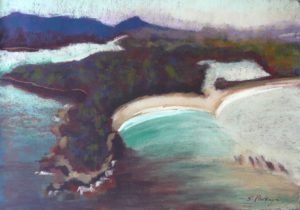

I could say that I found the story of Into the World through exploration, through inquisitiveness. When you first move to a new place you want to learn all you can about it. In 2010, I moved to Hobart, Tasmania and I started to explore. I went along the d’Entrecasteaux channel, past Bruny Island, through the Huon valley and down to Recherche Bay. All these names would later become familiar to me as the characters from my novel. I found plaques about the expedition, I saw artworks about the garden the French had planted and about the friendly first encounters between the French explorers and the Aboriginal people. I read about their visit to Recherche Bay in a magazine I picked up. I found a book of photographs by Bob Brown taken from the air at a time when he was trying to save the area from logging. Everywhere I went that year, it seemed that the story of these explorers was waiting for me to trip over it and take notice. I like to think that the story found me.

The words of the explorers first intrigued me – how they described the magnificent forests seemed to imply an understanding of ecology ahead of their time. The Commander, Bruni d’Entrecasteaux writes in his journal:

“Nature in all its vigour, and at the same time wasting away, seems to offer the imagination something more imposing and more vivid than the sight of the same nature embellished by industry and by civilized man; wanting to conserve only the beauty he has destroyed the charm; he has removed its unique character, that of being always ancient and always new.”

As an ecologist, I was already intrigued by this scientific expedition and there was something magical about the idea of reading the words of people visiting the place you were standing in, experiencing it for the first time, but from hundreds of years ago.

I was also interested in the gentle first encounters between the scientists and the hospitable Aboriginal people. I knew that in a few short decades after the visit, the Lyluequonny, Pangherninghe and Kumtemairrener people of the area would be decimated by disease and hunted from their lands by British settlers and sealers. This moment of shared humanity seemed to be a moment worth exploring, a celebration of mutual curiosity and an attempt to understand each other, a moment of hope before the brutal confrontations of colonisation to come.

And as I read more and more, I discovered that there was a woman on board the ship disguised as a man. A woman who was thought to be the first European woman to set foot in Tasmania. It seemed an amazing feat and I was drawn to the mystery of her story. What had compelled her to take this step into the unknown? The reason given in the memoirs of a shipmate was that she was fleeing the wrath of her father. I wanted to unpack what that meant. What that rage meant. Abandoned by a faithless lover and fleeing the wrath of her father. There must have been a child, and where was that child when Marie-Louise Girardin made this choice?

Marie-Louise left no account of her own, and is not mentioned at all in the official record of the voyage, it is only in the journals of her shipmates that we get glimpses of her life.

Here was a story that needed to be told, a story that deserved to be told from the perspective of someone who had no voice. And I am grateful the story found me to share it.